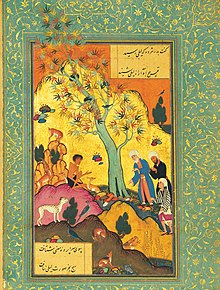

A scene from Nezami's adaptation of the story. Layla and Majnun meet for the last time before their deaths. Both have fainted and Majnun's elderly messenger attempts to revive Layla while wild animals protect the pair from unwelcome intruders. Late 16th century illustration. |

Layla and Majnun, also known as The Madman and Layla – in Arabic مجنون و ليلى (Majnun and Layla) or قيس وليلى (Qays and Layla), in Persian: لیلی و مجنون (Leyli o Majnun), Leyli və Məcnun in Azeri, Leyla ile Mecnun in Turkish, Hindustani: लैला मजनू لیلا مجنو (lailā majanū) – is a classical Arabic story. It is based on the real story of a young man called Qays ibn al-Mulawwah (Arabic: قيس بن الملوح) from Najd (the northern Arabian Peninsula) during the Umayyad era in the 7th century. In one version, he spent his youth together with Layla, tending their flocks. In another version, upon seeing Layla he fell passionately in love with her. In both versions, however, he went mad when her father prevented him from marrying her; for that reason he came to be called Majnun (Arabic: مجنون) meaning "madman."

Story

Qays ibn al-Mulawwah ibn Muzahim, was a Bedouin poet. He fell in love with Layla bint Mahdi ibn Sa’d (better known as Layla Al-Aamiriya) from the same tribe. He soon began composing poems about his love for her, mentioning her name often. When he asked for her hand in marriage, her father refused as this would mean a scandal for Layla according to local traditions. Soon after, Layla married another man.

When Qays heard of her marriage, he fled the tribe camp and began wandering the surrounding desert. His family eventually gave up hope for his return and left food for him in the wilderness. He could sometimes be seen reciting poetry to himself or writing in the sand with a stick.

Layla moved to present-day Iraq with her husband, where she became ill and eventually died. Qays was later found dead in the wilderness in 688 AD. near an unknown woman’s grave. He had carved three verses of poetry on a rock near the grave, which are the last three verses attributed to him.

Many other minor incidents happened between his madness and his death. Most of his recorded poetry was composed before his descent into madness.

Among the poems attributed to Qays ibn al-Mulawwah, regarding Layla:

“ I pass by these walls, the walls of Layla

And I kiss this wall and that wall

It’s not Love of the houses that has taken my heart

But of the One who dwells in those houses

”

It is a tragic story of undying love much like the later Romeo and Juliet. This type of love is known in Arabic culture as "Virgin Love" (Arabic: حب عذري), because the lovers never married or made love. Other famous Virgin Love stories are the stories of "Qays and Lubna", "Kuthair and Azza", "Marwa and Al Majnoun Al Faransi" and "Antara and Abla". The literary motif itself is common throughout the world, notably in the Muslim literature of South Asia, such as Urdu ghazals.

Variations

In India it is believed that Layla and Majnun found refuge in a village in Rajasthan before they died. The 'graves' of Layla and Majnun are believed to be located in the Bijnore village near Anupgarh in the Sriganganagar district. According to rural legend there, Layla and Majnun escaped to these parts and died there. Hundreds of newlyweds and lovers from India and Pakistan, despite there being no facilities for an overnight stay, attend the two day fair in June.

Another variation on the tale tells of Layla and Majnun meeting in school. Majnun fell in love with Layla and was captivated by her. The school master would beat Majnun for paying attention to Layla instead of his school work. However, upon some sort of magic, whenever Majnun was beaten, Layla would bleed for his wounds. Word reached their households and their families feuded. Separated at childhood, Layla and Majnun met again in their youth. Layla's brother, Tabrez, would not let Layla shame the family name by marrying Majnun. Tabrez and Majnun quarreled; stricken with madness over Layla, Majnun murdered Tabrez. Word reached the village and Majnun was arrested. He was sentenced to be stoned to death by the villagers. Layla could not bear it and agreed to marry another man if Majnun would be kept safe from harm in exile. Layla got married but her heart longed for Majnun. Hearing this, Layla's husband rode with his men to the desert towards Majnun. He challenged Majnun to the death. It is said that the instant Layla's husband's sword pierced Majnun's heart, Layla collapsed in her home. Layla and Majnun were said to be buried next to each other as her husband and their fathers prayed to their afterlife. Myth has it, Layla and Majnun met again in heaven, where they loved forever.

History and influence

Persian Adaptation and Persian literature

From Arab and Habib folklore the story was absorbed and embellished by Persian. The story of Lili o Majnoon was known in Persian at least from the time of Rudaki and Baba Taher who mentions the lovers.

Although the story was somewhat popular in Persian literature in the 12th century, it was the Persian masterpiece of Nezami Ganjavi that popularized it dramatically in Persian literature. Nezami collected both secular and mystical sources about Majnun and portrayed a vivid picture of the famous lovers . Subsequently, many other Persian poets imitated him and wrote their own versions of the romance. By collecting information from both secular and mystical sources about Majnun, Nizami portrayed such a vivid picture of this legendary lover that all subsequent poets were inspired by him, many of them imitated him and wrote their own versions of the romance. Nezami uses various characteristics deriving from 'Udhrite love poetry and weaves them into his own Persian culture. He Persianised the poem by adding techniques borrowed from the Persian epic tradition, such as "the portrayal of characters, the relationship between characters, description of time and setting, etc.".

In his adaptation, the young lovers become acquainted at school and fell desperately in love. However, they could not see each other due to a family feud, and Layla's family arranged for her to marry another man . According to Dr. Rudolf Gelpke: Many later poets have imitated Nizami's work, even if they could not equal and certainly not surpass it; Persians, Turks, Indians, to name only the most important ones. The Persian scholar Hekmat has listed not less than forty Persians and thirteen Turkish versions of Layli and Majnun. According to Vahid Dastgerdi, If one would search all existing libraries, one would probably find more than 1000 versions of Layli and Majnun.

In his statistical survey of famous Persian romances, Ḥasan Ḏulfaqāri enumerates 59 ‘imitations’ (naẓira s) of Leyli o Majnun as the most popular romance in the Iranian world, followed by 51 versions of Ḵosrow o Širin, 22 variants of Yusof o Zuleikha and 16 versions of Vāmeq oʿAḏrāʾ.

Azeri Adapation and Azerbaijani literature

The Story of Layla and Majnun passed into Azerbaijani literature. The Azerbaijani language adaptation of the story, Dâstân-ı Leylî vü Mecnûn (داستان ليلى و مجنون; "The Epic of Layla and Majnun") was written in the 16th century by Fuzûlî and Hagiri Tabrizi. Fuzûlî's version was borrowed by the renowned Azerbaijani composer Uzeyir Hajibeyov, who used the material to create what became the Middle East's first opera. It premiered in Baku on 25 January 1908. The story had previously been brought to the stage in the late 19th century, when Ahmed Shawqi wrote a poetic play about the tragedy, now considered one of the best in modern Arab poetry. Qays's lines from the play are sometimes confused with his actual poems.

A scene of the poem is depicted on the reverse of the Azerbaijani 100 and 50 manat commemorative coins minted in 1996 for the 500th anniversary of Fuzûlî's life and activities.

Other Influences

The enduring popularity of the legend has influenced Middle Eastern literature, especially Sufi writers, in whose literature the name Layla refers to their concept of the Beloved. The original story is featured in Bahá'u'lláh's mystical writings, the Seven Valleys. Etymologically, Layla is related to the Hebrew and Arabic words for "night," and is thought to mean "one who works by night." This is an apparent allusion to the fact that the romance of the star-crossed lovers was hidden and kept secret. In the Persian and Arabic languages, the word Majnun means "crazy." In addition to this creative use of language, the tale has also made at least one linguistic contribution, inspiring a Turkish colloquialism: to "feel like Mecnun" is to feel completely possessed, as might be expected of a person who is literally madly in love.

This epic poem was translated into English by Isaac D'Israeli in the early 19th century allowing a wider audience to appreciate it.

Layla has also been mentioned in many works by the notorious Aleister Crowley in many of his religious texts, perhaps most notably, in The Book of Lies.

Popular culture

The name "Layla" served as Clapton's inspiration for the title of Derek and the Dominos' famous album Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs and its title track. The song "I Am Yours" is a direct quote from a passage in Layla and Majnun.

The tale of Layla and Majnun has been the subject of various films produced by the Indian film industry beginning in the 1920s. A list may be found here: http://beta.thehindu.com/arts/cinema/article419176.ece. One, Laila Majnun, was produced in 1976. In 2007, the story was enacted as both a framing story and as a dance-within-a-movie in the film Aaja Nachle. There is a reference to the story in the song 'Laila' from the film Qurbani. Also, in pre-partition India, the first Pashto-language film was an adaptation of this story.

The term Layla-Majnun is often used for lovers, also Majnun is commonly used to address a person madly in love.

Orhan Pamuk makes frequent reference to Leyla and Majnun in his novel, The Museum of Innocence.

One of the panels in the Alisher Navoi metro station in Tashkent (Uzbekistan) and Nizami Gəncəvi metro station in Baku (Azerbaijan) represents the epic on blue green tiles.

In the book A Thousand Splendid Suns by Afghan author Khaled Hosseini, Rasheed often refers to Laila and Tariq as Layla and Majnun.

On Gaia Online, a recent monthly collectible released an item under the names Majnun and Layla loosely based on the story.(see also: http://www.gaiaonline.com/ or http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gaia_Online)

Layla and Majnun — poem of Alisher Navoi.

Layla and Majnun — poem of Jami.

Layla and Majnun — poem of Nizami Ganjavi.

Layla and Majnun — poem of Fuzûlî.

Layla and Majnun — poem of Hagiri Tabrizi.

Layla and Majnun — drama in verse of Mirza Hadi Ruswa.

Layla and Majnun — novel of Necati.

Layla and Majnun — the first Muslim and the Azerbaijani opera of Uzeyir Hajibeyov.

«Layla and Majnun» — symphonic poem of Gara Garayev (1947)

Symphony № 24 ("Majnun"), Op. 273 (1973), for tenor solo, violin, choir and chamber orchestra - Symphony Alan Hovanessa.

Layla and Majnun — ballet, staged by K. Goleizovsky (1964) © on music SA Balasanyan.

Layla and Majnun — Iranian film in 1936.

Layla and Majnun — Tajik Soviet film-ballet of 1960.

Layla and Majnun — Soviet Azerbaijani film of 1961.

Layla and Majnun — Indian film in 1976.

Layla and Majnun — Azerbaijani film-opera of 1996.

(source:wikipedia)

No comments:

Post a Comment