International human rights law, Human rights,

| Rights |

|---|

| Theoretical distinctions |

| Natural and legal rights Claim rights and liberty rights Negative and positive rights Individual and group rights |

| Human rights divisions |

| Three generations Civil and political Economic, social and cultural |

| Rights claimants |

| Animals · Humans Men · Women Fathers · Mothers Children · Youth · Fetuses · Students Indigenes · Minorities · LGBT |

| Other groups of rights |

| Authors' · Digital · Labor Linguistic · Reproductive |

Human rights are "rights and freedoms to which all humans are entitled". Proponents of the concept usually assert that everyone is endowed with certain entitlements merely by reason of being human. Human rights are thus conceived in a universalist and egalitarian fashion. Such entitlements can exist as shared norms of actual human moralities, as justified moral norms or natural rights supported by strong reasons, or as legal rights either at a national level or within international law. However, there is no consensus as to the precise nature of what in particular should or should not be regarded as a human right in any of the preceding senses, and the abstract concept of human rights has been a subject of intense philosophical debate and criticism.

The modern conception of human rights developed in the aftermath of the Second World War, in part as a response to the Holocaust, culminating in its adoption by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948. However, while the phrase "human rights" is relatively modern the intellectual foundations of the modern concept can be traced through the history of philosophy and the concepts of natural law rights and liberties as far back as the city states of Classical Greece and the development of Roman Law. The true forerunner of human rights discourse was the enlightenment concept of natural rights developed by figures such as John Locke and Immanuel Kant and through the political realm in the United States Bill of Rights and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

—Article 1 of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR)

History

The Magna Carta was issued in England in 1215.

Although ideas of rights and liberty have existed for much of human history, it is unclear to what degree such concepts can be described as "human rights" in the modern sense. The concept of rights certainly existed in pre-modern cultures; ancient philosophers such as Aristotle wrote extensively on the rights (to dikaion in ancient Greek, roughly a 'just claim') of citizens to property and participation in public affairs. However, neither the Greeks nor the Romans had any concept of universal human rights; slavery, for instance, was justified both in ancient and modern times as a natural condition. Medieval charters of liberty such as the English Magna Carta were not charters of human rights, let alone general charters of rights: they instead constituted a form of limited political and legal agreement to address specific political circumstances, in the case of Magna Carta later being mythologised in the course of early modern debates about rights.

The basis of most modern legal interpretations of human rights can be traced back to recent European history. The Twelve Articles (1525) are considered to be the first record of human rights in Europe. They were part of the peasants' demands raised towards the Swabian League in the German Peasants' War in Germany. In Britain in 1689, the English Bill of Rights (or “An Act Declaring the Rights and Liberties of the Subject and Settling the Succession of the Crown”) and the Scottish Claim of Right each made illegal a range of oppressive governmental actions. Two major revolutions occurred during the 18th century, in the United States (1776) and in France (1789), leading to the adoption of the United States Declaration of Independence and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen respectively, both of which established certain legal rights. Additionally, the Virginia Declaration of Rights of 1776 encoded into law a number of fundamental civil rights and civil freedoms.

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen approved by the National Assembly of France, August 26, 1789.

“ We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. ”

—United States Declaration of Independence, 1776

These were followed by developments in philosophy of human rights by philosophers such as Thomas Paine, John Stuart Mill and G. W. F. Hegel during the 18th and 19th centuries. The term human rights probably came into use sometime between Paine's The Rights of Man and William Lloyd Garrison's 1831 writings in The Liberator saying he was trying to enlist his readers in "the great cause of human rights"

In the 19th century, human rights became a central concern over the issue of slavery. A number of reformers such as William Wilberforce in Britain, worked towards the abolition of slavery. This was achieved in the British Empire by the Slave Trade Act 1807 and the Slavery Abolition Act 1833. In the United States, many northern states abolished their institution of slavery by the mid 19th century, although southern states were still very much economically dependent on slave labour. Conflict and debates over the expansion of slavery to new territories culminated in the southern states' secession and the American Civil War. During the reconstruction period immediately following the war, several amendments to the United States Constitution were made. These included the 13th amendment, banning slavery, 14th amendment, assuring full citizenship and civil rights to all people born in the United States, and the 15th amendment, guaranteeing African Americans the right to vote.

Many groups and movements have managed to achieve profound social changes over the course of the 20th century in the name of human rights. In Western Europe and North America, labour unions brought about laws granting workers the right to strike, establishing minimum work conditions and forbidding or regulating child labour. The women's rights movement succeeded in gaining for many women the right to vote. National liberation movements in many countries succeeded in driving out colonial powers. One of the most influential was Mahatma Gandhi's movement to free his native India from British rule. Movements by long-oppressed racial and religious minorities succeeded in many parts of the world, among them the African American Civil Rights Movement, and more recent diverse identity politics movements, on behalf of women and minorities in the United States.

The establishment of the International Committee of the Red Cross, the 1864 Lieber Code and the first of the Geneva Conventions in 1864 laid the foundations of International humanitarian law, to be further developed following the two World Wars.

The World Wars, and the huge losses of life and gross abuses of human rights that took place during them were a driving force behind the development of modern human rights instruments. The League of Nations was established in 1919 at the negotiations over the Treaty of Versailles following the end of World War I. The League's goals included disarmament, preventing war through collective security, settling disputes between countries through negotiation, diplomacy and improving global welfare. Enshrined in its charter was a mandate to promote many of the rights that were later included in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

At the 1945 Yalta Conference, the Allied Powers agreed to create a new body to supplant the League's role; this body was to be the United Nations. The United Nations has played an important role in international human-rights law since its creation. Following the World Wars, the United Nations and its members developed much of the discourse and the bodies of law that now make up international humanitarian law and international human rights law.

International human rights law

Modern international conceptions of human rights can be traced to the aftermath of World War II and the foundation of the United Nations. Article 1(3) of the United Nations charter set out one of the purposes of the UN is to: "o achieve international cooperation in solving international problems of an economic, social, cultural, or humanitarian character, and in promoting and encouraging respect for human rights and for fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion" The rights espoused in the UN charter would be codified in the International Bill of Human Rights, composing the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

"It is not a treaty...[In the future, it] may well become the international Magna Carta."[9] Eleanor Roosevelt with the Spanish text of the Universal Declaration in 1949.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948, partly in response to the atrocities of World War II. Although the UDHR was a non-binding resolution, it is now considered to have acquired the force of international customary law which may be invoked under appropriate circumstances by national and other judiciaries. The UDHR urges member nations to promote a number of human, civil, economic and social rights, asserting these rights are part of the "foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world." The declaration was the first international legal effort to limit the behaviour of states and press upon them duties to their citizens following the model of the rights-duty duality.

“ ...recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world ”

—Preamble to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948

The UDHR was framed by members of the Human Rights Commission, with former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt as Chair, who began to discuss an International Bill of Rights in 1947. The members of the Commission did not immediately agree on the form of such a bill of rights, and whether, or how, it should be enforced. The Commission proceeded to frame the UDHR and accompanying treaties, but the UDHR quickly became the priority. Canadian law professor John Humphrey and French lawyer René Cassin were responsible for much of the cross-national research and the structure of the document respectively, where the articles of the declaration were interpretative of the general principle of the preamble. The document was structured by Cassin to include the basic principles of dignity, liberty, equality and brotherhood in the first two articles, followed successively by rights pertaining to individuals; rights of individuals in relation to each other and to groups; spiritual, public and political rights; economic, social and cultural rights. The final three articles place, according to Cassin, rights in the context of limits, duties and the social and political order in which they are to be realized. Humphrey and Cassin intended the rights in the UDHR to be legally enforceable through some means, as is reflected in the third clause of the preamble:

“ Whereas it is essential, if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human rights should be protected by the rule of law. ”

—Preamble to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948

Some of the UDHR was researched and written by a committee of international experts on human rights, including representatives from all continents and all major religions, and drawing on consultation with leaders such as Mahatma Gandhi. The inclusion of civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights was predicated on the assumption that basic human rights are indivisible and that the different types of rights listed are inextricably linked. This principle was not then opposed by any member states (the declaration was adopted unanimously, with the abstention of the Eastern Bloc, Apartheid South Africa and Saudi Arabia), however this principle was later subject to significant challenges.

The Universal Declaration was bifurcated into two distinct and different covenants, a Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and a second Covenant on social, economic, and cultural rights due to questions about the relevance and propriety of economic and social provisions in covenants on human rights. Both covenants begin with the right of people to self-determination and to sovereignty over their natural resources. This debate over whether human rights are more fundamental than economic has continued to this day.

The drafters of the Covenants initially intended only one instrument. The original drafts included only political and civil rights, but economic and social rights were also proposed. The disagreement over which rights were basic human rights resulted in there being two covenants. The debate was whether economic and social rights are aspirational, as contrasted with basic human right which all people possess purely by being human, because economic and social rights depend on wealth and the availability of resources. In addition, which social and economic rights should be recognised depends on ideology or economic theories, in contrast to basic human rights which are defined purely by the nature (mental and physical abilities) of human beings. It was debated whether economic rights were appropriate subjects for binding obligations and whether the lack of consensus over such rights would dilute the strength of political-civil rights. There was wide agreement and clear recognition that the means required to enforce or induce compliance with socio-economic undertakings were different from the means required for civil-political rights.

This debate and the desire for the greatest number of signatories to human rights law led to the two covenants. The Soviet bloc and a number of developing countries had argued for the inclusion of all rights in a so-called Unity Resolution. The two covenants allowed states to adopt some rights and derogate others. Those in favor of having economic and social rights included with basic human rights could not gain sufficient consensus, despite their belief that all categories of rights should be linked.

Treaties

In 1966, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) were adopted by the United Nations, between them making the rights contained in the UDHR binding on all states that have signed this treaty, creating human rights law.

Since then numerous other treaties (pieces of legislation) have been offered at the international level. They are generally known as human rights instruments. Some of the most significant, referred to (with ICCPR and ICESCR) as "the seven core treaties", are:

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD) (adopted 1966, entry into force: 1969)

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) (entry into force: 1981)

United Nations Convention Against Torture (CAT) (adopted 1984, entry into force: 1984)

Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) (adopted 1989, entry into force: 1989)

Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) (adopted 2006, entry into force: 2008)

International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families (ICRMW or more often MWC) (adopted 1990, entry into force: 2003)

Humanitarian Law

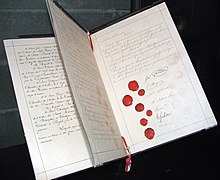

Original Geneva Convention in 1864.

Geneva Conventions and Humanitarian law

The Geneva Conventions came into being between 1864 and 1949 as a result of efforts by Henry Dunant, the founder of the International Committee of the Red Cross. The conventions safeguard the human rights of individuals involved in armed conflict, and build on the 1899 and 1907 Hague Conventions, the international community's first attempt to formalize the laws of war and war crimes in the nascent body of secular international law. The conventions were revised as a result of World War II and readopted by the international community in 1949.

Universal jurisdiction

Universal jurisdiction is a controversial principle in international law whereby states claim criminal jurisdiction over persons whose alleged crimes were committed outside the boundaries of the prosecuting state, regardless of nationality, country of residence, or any other relation with the prosecuting country. The state backs its claim on the grounds that the crime committed is considered a crime against all, which any state is authorized to punish. The concept of universal jurisdiction is therefore closely linked to the idea that certain international norms are erga omnes, or owed to the entire world community, as well as the concept of jus cogens.

International organizations

United Nations

The UN General Assembly

The United Nations (UN) is the only multilateral governmental agency with universally accepted international jurisdiction for universal human rights legislation. Human rights are primarily governed by the United Nations Security Council and the United Nations Human Rights Council, and there are numerous committees within the UN with responsibilities for safeguarding different human rights treaties. The most senior body of the UN with regard to human rights is the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. The United Nations has an international mandate to:

“ ...achieve international co-operation in solving international problems of an economic, social, cultural, or humanitarian character, and in promoting and encouraging respect for human rights and for fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, gender, language, or religion. ”

—Article 1–3 of the United Nations Charter

Human Rights Council

United Nations Human Rights Council logo.

United Nations Human Rights Council

The United Nations Human Rights Council, created at the 2005 World Summit to replace the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, has a mandate to investigate violations of human rights. The Human Rights Council is a subsidiary body of the General Assembly and reports directly to it. It ranks below the Security Council, which is the final authority for the interpretation of the United Nations Charter. Forty-seven of the one hundred ninety-one member states sit on the council, elected by simple majority in a secret ballot of the United Nations General Assembly. Members serve a maximum of six years and may have their membership suspended for gross human rights abuses. The Council is based in Geneva, and meets three times a year; with additional meetings to respond to urgent situations.

Independent experts (rapporteurs) are retained by the Council to investigate alleged human rights abuses and to provide the Council with reports.

The Human Rights Council may request that the Security Council take action when human rights violations occur. This action may be direct actions, may involve sanctions, and the Security Council may also refer cases to the International Criminal Court (ICC) even if the issue being referred is outside the normal jurisdiction of the ICC.

Security Council

United Nations Security Council.

The United Nations Security Council has the primary responsibility for maintaining international peace and security and is the only body of the UN that can authorize the use of force (including in the context of peace-keeping operations), or override member nations sovereignty by issuing binding Security Council resolutions. Created by the UN Charter, it is classed as a Charter Body of the United Nations. The UN Charter gives the Security Council the power to:

Investigate any situation threatening international peace;

Recommend procedures for peaceful resolution of a dispute;

Call upon other member nations to completely or partially interrupt economic relations as well as sea, air, postal, and radio communications, or to sever diplomatic relations; and

Enforce its decisions militarily if necessary.

The Security Council hears reports from all organs of the United Nations, and can take action over any issue which it feels threatens peace and security, including human rights issues. It has at times been criticised for failing to take action to prevent human rights abuses, including the Darfur crisis, the Srebrenica massacre and the Rwandan Genocide.

The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court recognizes the Security Council as having the power to refer cases to the Court, where the Court could not otherwise exercise jurisdiction.

On April 28, 2006 the Security Council adopted resolution 1674 that "Reaffirm the provisions of paragraphs 138 and 139 of the 2005 World Summit Outcome Document regarding the responsibility to protect populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity" and committed the Security Council to action to protect civilians in armed conflict.

Other UN Treaty Bodies

A modern interpretation of the original Declaration of Human Rights was made in the Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action adopted by the World Conference on Human Rights in 1993. The degree of unanimity over these conventions, in terms of how many and which countries have ratified them varies, as does the degree to which they are respected by various states. The UN has set up a number of treaty-based bodies to monitor and study human rights, to be supported by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCHR). The bodies are committees of independent experts that monitor implementation of the core international human rights treaties. They are created by the treaty that they monitor, except CESCR.

The Human Rights Committee promotes participation with the standards of the ICCPR. The eighteen members of the committee express opinions on member countries and make judgements on individual complaints against countries which have ratified an Optional Protocol to the treaty. The judgements, termed "views", are not legally binding.

The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights monitors the ICESCR and makes general comments on ratifying countries performance. It will have the power to receive complaints against the countries that opted into the Optional Protocol once it has come into force.

The Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination monitors the CERD and conducts regular reviews of countries' performance. It can make judgements on complaints against member states allowing it, but these are not legally binding. It issues warnings to attempt to prevent serious contraventions of the convention.

The Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women monitors the CEDAW. It receives states' reports on their performance and comments on them, and can make judgements on complaints against countries which have opted into the 1999 Optional Protocol.

The Committee Against Torture monitors the CAT and receives states' reports on their performance every four years and comments on them. Its subcommittee may visit and inspect countries which have opted into the Optional Protocol.

The Committee on the Rights of the Child monitors the CRC and makes comments on reports submitted by states every five years. It does not have the power to receive complaints.

The Committee on Migrant Workers was established in 2004 and monitors the ICRMW and makes comments on reports submitted by states every five years. It will have the power to receive complaints of specific violations only once ten member states allow it.

The Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities was established in 2008 to monitor the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. It has the power to receive complaints against the countries which have opted into the Optional Protocol.

Each treaty body receives secretariat support from the Human Rights Council and Treaties Division of Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights (OHCHR) in Geneva except CEDAW, which is supported by the Division for the Advancement of Women (DAW). CEDAW formerly held all its sessions at United Nations headquarters in New York but now frequently meets at the United Nations Office in Geneva; the other treaty bodies meet in Geneva. The Human Rights Committee usually holds its March session in New York City.

Nongovernmental Organizations

International Nongovernmental human rights organizations such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and FIDH promote and monitor human rights around the world. Human Rights organizations ""translate complex international issues into activities to be undertaken by concerned citizens in their own community" Human rights organisations frequently engage in lobbying and advocacy in an effort to convince the united nations, supranational bodies and national governments to respect human rights. Many Human rights organisations have observer status at the various united nations bodies tasked with protecting human rights.The most prominent nongovernmental human rights conference is the Oslo Freedom Forum, a gathering described by The Economist as “on its way to becoming a human-rights equivalent of the Davos economic forum.”

Regional human rights

The three principal regional human rights instruments are the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights, the American Convention on Human Rights (the Americas) and the European Convention on Human Rights.

See also

(source:wikipedia)

No comments:

Post a Comment