An analog computer is a form of computer that uses the continuously-changeable aspects of physical phenomena such as electrical, mechanical, or hydraulic quantities to model the problem being solved. In contrast, digital computers represent varying quantities incrementally, as their numerical values change.Mechanical analog computers were very important in gun fire control in World War II and the Korean War; they were made in significant numbers. In particular, development of transistors made electronic analog computers practical, and before digital computers had developed sufficiently, they were commonly used in science and industry.

Analog computers can have a very wide range of complexity. Slide rules and nomographs are the simplest, while naval gunfire control computers and large hybrid digital/analog computers were among the most complicated.

Setting up an analog computer required scale factors to be chosen, along with initial conditions—that is, starting values. Another essential was creating the required network of interconnections between computing elements. Sometimes it was necessary to re-think the structure of the problem so that the computer would function satisfactorily. No variables could be allowed to exceed the computer's limits, and differentiation was to be avoided, typically by rearranging the "network" of interconnects, using integrators in a different sense.

Running an electronic analog computer, assuming a satisfactory setup, started with the computer held with some variables fixed at their initial values. Moving a switch released the holds and permitted the problem to run. In some instances, the computer could, after a certain running time interval, repeatedly return to the initial-conditions state to reset the problem, and run it again.

Timeline of analog computers

The Antikythera mechanism is believed to be the earliest known mechanical analog computer. It was designed to calculate astronomical positions. It was discovered in 1901 in the Antikythera wreck off the Greek island of Antikythera, between Kythera and Crete, and has been dated to circa 100 BC. Devices of a level of complexity comparable to that of the Antikythera mechanism would not reappear until a thousand years later.

The astrolabe was invented in the Hellenistic world in either the 1st or 2nd centuries BC and is often attributed to Hipparchus. A combination of the planisphere and dioptra, the astrolabe was effectively an analog computer capable of working out several different kinds of problems in spherical astronomy. An astrolabe incorporating a mechanical calendar computer and gear-wheels was invented by Abi Bakr of Isfahan in 1235.

Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī invented the first mechanical geared lunisolar calendar astrolabe, an early fixed-wired knowledge processing machine with a gear train and gear-wheels, circa 1000 AD.

The Planisphere was a star chart astrolabe invented by Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī in the early 11th century.

The castle clock, an astronomical clock invented by Al-Jazari in 1206, has been described by some as the first programmable analog computer. It displayed the zodiac, the solar and lunar orbits, a crescent moon-shaped pointer travelling across a gateway causing automatic doors to open every hour, and five robotic musicians who play music when struck by levers operated by a camshaft attached to a water wheel. The length of day and night could be re-programmed every day in order to account for the changing lengths of day and night throughout the year.

A slide rule

The slide rule is a hand-operated analog computer for doing (at least) multiplication and division, invented around 1620–1630, shortly after the publication of the concept of the logarithm. As slide rule development progressed, added scales provided reciprocals, squares and square roots, cubes and cube roots, as well as transcendental functions such as logarithms and exponentials, circular and hyperbolic trigonometry and other functions .

The differential analyser, a mechanical analog computer designed to solve differential equations by integration, using wheel-and-disc mechanisms to perform the integration. Invented in 1876 by James Thomson, they were first built in the 1920s and 1930s. Extensions and enhancements were the basis of some parts of mechanical analog gun fire control computers.

By 1912 Arthur Pollen had developed an electrically driven mechanical analog computer for fire-control systems, based on the differential analyser. It was used by the Imperial Russian Navy in World War I.

World War II era gun directors, gun data computers, and bomb sights used mechanical analog computers.

The FERMIAC was an analog computer invented by physicist Enrico Fermi in 1947 to aid in his studies of neutron transport.

The MONIAC Computer was a hydraulic model of a national economy first unveiled in 1949.

Computer Engineering Associates was spun out of Caltech in 1950 to provide commercial services using the "Direct Analogy Electric Analog Computer" ("the largest and most impressive general-purpose analyzer facility for the solution of field problems") developed there by Gilbert D. McCann, Charles H. Wilts, and Bart Locanthi.

Heathkit EC-1, a $199 educational analog computer made by the Heath Company, USA c. 1960. It was programmed using patch cords that connected nine operational amplifiers and other components

General Electric also marketed an "educational" analog computer kit of a simple design in the early 1960s consisting of a two transistor tone generator and three potentiometers wired such that the frequency of the oscillator was nulled when the potentiometer dials were positioned by hand to satisfy an equation. The relative resistance of the potentiometer was then equivalent to the formula of the equation being solved. Multiplication or division could be performed depending on which dials were considered inputs and which was the output. Accuracy and resolution was, of course, extremely limited and a simple slide rule was more accurate, however, the unit did demonstrate the basic principle.

Electronic analog computers

Polish analog computer AKAT-1.

The similarity between linear mechanical components, such as springs and dashpots (viscous-fluid dampers), and electrical components, such as capacitors, inductors, and resistors is striking in terms of mathematics. They can be modeled using equations that are of essentially the same form.

However, the difference between these systems is what makes analog computing useful. If one considers a simple mass-spring system, constructing the physical system would require making or modifying the springs and masses. This would be followed by attaching them to each other and an appropriate anchor, collecting test equipment with the appropriate input range, and finally, taking measurements. In more complicated cases, such as suspensions for racing cars, experimental construction, modification, and testing is not so simple nor inexpensive.

The electrical equivalent can be constructed with a few operational amplifiers (Op amps) and some passive linear components; all measurements can be taken directly with an oscilloscope. In the circuit, the (simulated) 'stiffness of the spring', for instance, can be changed by adjusting a potentiometer. The electrical system is an analogy to the physical system, hence the name, but it is less expensive to construct, generally safer, and typically much easier to modify.

As well, an electronic circuit can typically operate at higher frequencies than the system being simulated. This allows the simulation to run faster than real time (which could, in some instances, be hours, weeks, or longer). Experienced users of electronic analog computers said that they offered a comparatively intimate control and understanding of the problem, relative to digital simulations.

The drawback of the mechanical-electrical analogy is that electronics are limited by the range over which the variables may vary. This is called dynamic range. They are also limited by noise levels. Floating-point digital calculations have comparatively-huge dynamic range (good modern handheld scientific/engineering calculators have exponents of 500).

These electric circuits can also easily perform a wide variety of simulations. For example, voltage can simulate water pressure and electric current can simulate rate of flow in terms of cubic metres per second (in fact, given the proper scale factors, all that is required would be a stable resistor, in that case). Given flow rate and accumulated volume of liquid, a simple integrator provides the latter; both variables are voltages. In practice, current was rarely used in electronic analog computers, because voltage is much easier to work with.

Analog computers are especially well-suited to representing situations described by differential equations. Occasionally, they were used when a differential equation proved very difficult to solve by traditional means.

An electronic digital system uses two voltage levels to represent binary numbers. In many cases, the binary numbers are simply codes that correspond, for instance, to brightness of primary colors, or letters of the alphabet (or other symbols). The manipulation of these binary numbers is how digital computers work. The electronic analog computer, however, manipulates electrical voltages that are proportional to the magnitudes of quantities in the problem being solved.

Accuracy of an analog computer is limited by its computing elements as well as quality of the internal power and electrical interconnections. The precision of the analog computer readout was limited chiefly by the precision of the readout equipment used, generally three or four significant figures. Precision of a digital computer is limited by the word size; arbitrary-precision arithmetic, while relatively slow, provides any practical degree of precision that might be needed.

Analog-digital hybrid computers

There is an intermediate device, a 'hybrid' computer, in which an analog output is converted into digits. The information then can be sent into a standard digital computer for further computation. Because of their ease of use and because of technological breakthroughs in digital computers in the early 70s, the analog-digital hybrids were replacing the analog-only systems.

Hybrid computers are used to obtain a very accurate but not very mathematically precise 'seed' value, using an analog computer front-end, which value is then fed into a digital computer, using an iterative process to achieve the final desired degree of precision. With a three or four digit precision, highly-accurate numerical seed, the total computation time necessary to reach the desired precision is dramatically reduced, since many fewer digital iterations are required (and the analog computer reaches its result almost instantaneously). Or, for example, the analog computer might be used to solve a non-analytic differential equation problem for use at some stage of an overall computation (where precision is not very important). In any case, the hybrid computer is usually substantially faster than a digital computer, but can supply a far more precise computation than an analog computer. It is useful for real-time applications requiring such a combination (e.g., a high frequency phased-array radar or a weather system computation).

Polish Analog computer ELWAT.

Mechanisms

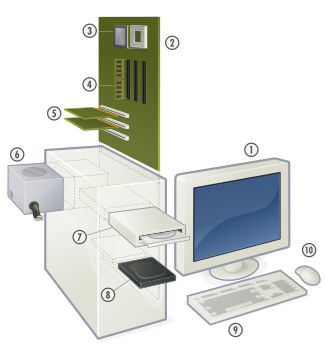

Electronic analog computers typically have front panels with numerous jacks (single-contact sockets) that permit patch cords (flexible wires with plugs at both ends) to create the interconnections which define the problem setup. In addition, there are precision high-resolution potentiometers (variable resistors) for setting up (and, when needed, varying) scale factors. In addition, there is likely to be a zero-center analog pointer-type meter for modest-accuracy voltage measurement. Stable, accurate voltage sources provide known magnitudes.

Typical electronic analog computers contain anywhere from a few to a hundred or more operational amplifiers ("op amps"), named because they perform mathematical operations. Op amps are a particular type of feedback amplifier with very high gain and stable input (low and stable offset). They are always used with precision feedback components that, in operation, all but cancel out the currents arriving from input components. The majority of op amps in a representative setup are summing amplifiers, which add and subtract analog voltages, providing the result at their output jacks. As well, op amps with capacitor feedback are usually included in a setup; they integrate the sum of their inputs with respect to time.

Integrating with respect to another variable is the nearly-exclusive province of mechanical analog integrators; it is almost never done in electronic analog computers. However, given that a problem solution does not change with time, time can serve as one of the variables.

Other computing elements include analog multipliers, nonlinear function generators, and analog comparators.

Inductors were never used in typical electronic analog computers, because their departure from ideal behavior is too great for computing of any great accuracy. Analog computer setups that at first would seem to require inductors can be rearranged and redefined to use capacitors. Capacitors and resistors, on the other hand, can be made much closer to ideal than inductors, which is why they constitute the majority of passive computing components.

The use of electrical properties in analog computers means that calculations are normally performed in real time (or faster), at a speed determined mostly by the frequency response of the operational amplifiers and other computing elements. In the history of electronic analog computers, there were some special high-speed types.

Nonlinear functions and calculations can be constructed to a limited precision (three or four digits) by designing function generators — special circuits of various combinations of resistors and diodes to provide the nonlinearity. Typically, as the input voltage increases, progressively more diodes conduct.

When compensated for temperature, the forward voltage drop of a transistor's base-emitter junction can provide a usably-accurate logarithmic or exponential function. Op amps scale the output voltage so that it is usable with the rest of the computer.

Any physical process which models some computation can be interpreted as an analog computer. Some examples, invented for the purpose of illustrating the concept of analog computation, include using a bundle of spaghetti as a model of sorting numbers; a board, a set of nails, and a rubber band as a model of finding the convex hull of a set of points; and strings tied together as a model of finding the shortest path in a network. These are all described in A.K. Dewdney (see citation below).

Mechanical analog computer mechanisms

While a wide variety of mechanisms have been developed throughout history, some stand out because of their theoretical importance, or because they were manufactured in significant quantities.

Most practical mechanical analog computers of any significant complexity used rotating shafts to carry variables from one mechanism to another. Cables and pulleys were used in a Fourier synthesizer, a tide-predicting machine, which summed the individual harmonic components. Another category, not nearly as well known, used rotating shafts only for input and output, with precision racks and pinions. The racks were connected to linkages that performed the computation. At least one US Naval sonar fire control computer of the later 1950s, made by Librascope, was of this type, as was the principal computer in the Mk. 56 Gun Fire Control System.

Online, there is a remarkably-clear illustrated reference (OP 1140) that describes World War II mechanical analog fire control computer mechanisms. Lacking access to OP 1140, a text description of many important mechanisms follows.

For adding and subtracting, precision miter-gear differentials were in common use in some computers; the Ford Instrument Mk 1 Fire Control Computer contained about 160 of them.

Integration with respect to another variable was done by a rotating disc driven by one variable. Output came from a pickoff device (such as a wheel) positioned at a radius on the disc proportional to the second variable. (A carrier with a pair of steel balls supported by small rollers worked especially well. A roller, its axis parallel to the disc's surface, provided the output. It was held against the pair of balls by a spring.)

Arbitrary functions of one variable were provided by cams, with gearing to convert follower movement to shaft rotation.

Functions of two variables were provided by three-dimensional cams. In one good design, one of the variables rotated the cam. A hemispherical follower moved its carrier on a pivot axis parallel to that of the cam's rotating axis. Pivoting motion was the output. The second variable moved the follower along the axis of the cam. One practical application was ballistics in gunnery.

Coordinate conversion from polar to rectangular was done by a mechanical resolver (called a "component solver" in US Navy fire control computers). Two discs on a common axis positioned a sliding block with pin (stubby shaft) on it. One disc was a face cam, and a follower on the block in the face cam's groove set the radius. The other disc, closer to the pin, contained a straight slot in which the block moved. The input angle rotated the latter disc (the face cam disc, for an unchanging radius, rotated with the other (angle) disc; a differential and a few gears did this correction).

Referring to the mechanism's frame, the location of the pin corresponded to the tip of the vector represented by the angle and magnitude inputs. Mounted on that pin was a square block.

Rectilinear-coordinate outputs (both sine and cosine, typically) came from two slotted plates, each slot fitting on the block just mentioned. The plates moved in straight lines, the movement of one plate at right angles to that of the other. The slots were at right angles to the direction of movement. Each plate, by itself, was like a Scotch yoke, known to steam engine enthusiasts.

During World War II, a similar mechanism converted rectilinear to polar coordinates, but it was not particularly successful and was eliminated in a significant redesign (USN, Mk. 1 to Mk. 1A).

Multiplication was done by mechanisms based on the geometry of similar right triangles. Using the trig. terms for a right triangle, specifically opposite, adjacent, and hypotenuse, the adjacent side was fixed by construction. One variable changed the magnitude of the opposite side. In many cases, this variable changed sign; the hypotenuse could coincide with the adjacent side (a zero input), or move beyond the adjacent side, representing a sign change.

Typically, a pinion-operated rack moving parallel to the (trig.-defined) opposite side would position a slide with a slot coincident with the hypotenuse. A pivot on the rack let the slide's angle change freely. At the other end of the slide (the angle, in trig, terms), a block on a pin fixed to the frame defined the vertex between the hypotenuse and the adjacent side.

At any distance along the adjacent side, a line perpendicular to it intersects the hypotenuse at a particular point. The distance between that point and the adjacent side is some fraction that is the product of 1 the distance from the vertex, and 2 the magnitude of the opposite side.

The second input variable in this type of multiplier positions a slotted plate perpendicular to the adjacent side. That slot contains a block, and that block's position in its slot is determined by another block right next to it. The latter slides along the hypotenuse, so the two blocks are positioned at a distance from the (trig.) adjacent side by an amount proportional to the product.

To provide the product as an output, a third element, another slotted plate, also moves parallel to the (trig.) opposite side of the theoretical triangle. As usual, the slot is perpendicular to the direction of movement. A block in its slot, pivoted to the hypotenuse block positions it.

A special type of integrator, used at a point where only moderate accuracy was needed, was based on a steel ball, instead of a disc. It had two inputs, one to rotate the ball, and the other to define the angle of the ball's rotating axis. That axis was always in a plane that contained the axes of two movement-pickoff rollers, quite similar to the mechanism of a rolling-ball computer mouse (in this mechanism, the pickoff rollers were roughly the same diameter as the ball). The pickoff roller axes were at right angles.

A pair of rollers "above" and "below" the pickoff plane were mounted in rotating holders that were geared together. That gearing was driven by the angle input, and established the rotating axis of the ball. The other input rotated the "bottom" roller to make the ball rotate.

Essentially, the whole mechanism, called a component integrator, was a variable-speed drive with one motion input and two outputs, as well as an angle input. The angle input varied the ratio (and direction) of coupling between the "motion" input and the outputs according to the sine and cosine of the input angle.

Although they were did not accomplish any computation, electromechanical position servos were essential in mechanical analog computers of the "rotating-shaft" type for providing operating torque to the inputs of subsequent computing mechanisms, as well as driving output data-transmission devices such as large torque-transmitter synchros in naval computers.

Other non-computational mechanisms included internal odometer-style counters with interpolating drum dials for indicating internal variables, and mechanical multi-turn limit stops.

Considering that accurately-controlled rotational speed in analog fire-control computers was a basic element of their accuracy, there was a motor with its average speed controlled by a balance wheel, hairspring, jeweled-bearing differential, a twin-lobe cam, and spring-loaded contacts (ship's AC power frequency was not necessarily accurate, nor dependable enough, when these computers were designed).

Components

A 1960 Newmark analogue computer, made up of five units. This computer was used to solve differential equations and is currently housed at the Cambridge Museum of Technology.

Analog computers often have a complicated framework, but they have, at their core, a set of key components which perform the calculations, which the operator manipulates through the computer's framework.

Key hydraulic components might include pipes, valves and containers.

Key mechanical components might include rotating shafts for carrying data within the computer, miter-gear differentials, disc/ball/roller integrators, cams (2-D and 3-D), mechanical resolvers and multipliers, and torque servos.

Key electrical/electronic components might include:

Precision resistors and capacitors

operational amplifiers

Multipliers

potentiometers

fixed-function generators

The core mathematical operations used in an electric analog computer are:

summation

integration with respect to time

inversion

multiplication

exponentiation

logarithm

division, although multiplication is much preferred

Differentiation with respect to time is not frequently used, and in practice is avoided by redefining the problem when possible. It corresponds in the frequency domain to a high-pass filter, which means that high-frequency noise is amplified; differentiation also risks instability.

Limitations

In general, analog computers are limited by non-ideal effects. An analog signal is composed of four basic components: DC and AC magnitudes, frequency, and phase. The real limits of range on these characteristics limit analog computers. Some of these limits include the operational amplifier offset, finite gain, and frequency response, noise floor, non-linearities, temperature coefficient, and parasitic effects within semiconductor devices. For commercially available electronic components, ranges of these aspects of input and output signals are always figures of merit.

Current research

Although digital computation is extremely popular, some research in analog computation is still being done. A few universities still use analog computers to teach control system theory. Comdyna manufactured small analog computers until roughly the end of the 20th century. At Indiana University Bloomington, Jonathan Mills has developed the Extended Analog Computer based on sampling voltages in a foam sheet. At the Harvard Robotics Laboratory, analog computation is a research topic.

Practical examples

These are examples of analog computers that have been constructed or practically used:

Antikythera mechanism

astrolabe

differential analyzer

Deltar

Kerrison Predictor

mechanical integrators, fo example, the planimeter

MONIAC Computer (hydraulic model of UK economy)

nomogram

Norden bombsight

Rangekeeper and related fire control computers

slide rule

tide-predicting machine

Torpedo Data Computer

Torquetum

Water integrator

Mechanical computer

Analog (music) synthesizers can also be viewed as a form of analog computer, and their technology was originally based in part on electronic analog computer technology. The ARP 2600's Ring Modulator was actually an moderate-accuracy analog multiplier.

The Simulation Council (or Simulations Council) was an association of analog computer users in USA. It is now known as the The Society of Modeling and Simulation International. The Simulation Council newsletters from 1952 to 1963 are available online and show the concerns and technologies at the time, and the common use of analog computers for missilry.

Real computers

Computer theorists often refer to idealized analog computers as real computers (because they operate on the set of real numbers). Digital computers, by contrast, must first quantize the signal into a finite number of values, and so can only work with the rational number set (or, with an approximation of irrational numbers).

These idealized analog computers may in theory solve problems that are intractable on digital computers; however as mentioned, in reality, analog computers are far from attaining this ideal, largely because of noise minimization problems. In theory, ambient noise is limited by quantum noise (caused by the quantum movements of ions). Ambient noise may be severely reduced — but never to zero — by using cryogenically cooled parametric amplifiers. Moreover, given unlimited time and memory, the (ideal) digital computer may also solve real number problems.

(source:wikpedia)